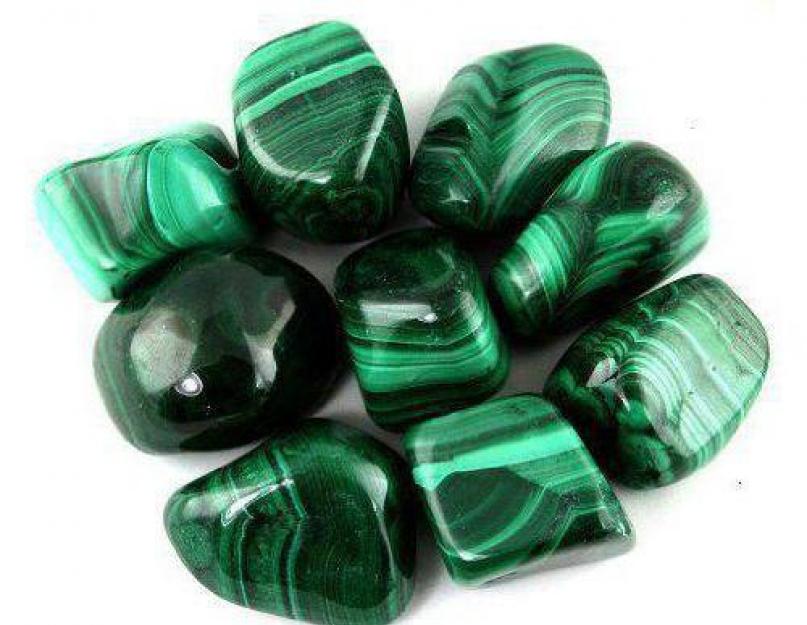

Malachite is one of the most beautiful minerals. Its color is rich in shades - the whole palette of green tones is from light green with blue (turquoise) to a dense dark green color ("pleated"). The mineral received the name, probably, for its green color, reminiscent of the color of mallow leaves (Greek "malache" - "mallow"), or for its low hardness (Greek. "Malakos" - "soft").

In medieval Europe and in Ancient Russia, the Latin "molochites" had a synonym - "murrin". In the scientific everyday life in the XVII century. used variations of Plinyevsky "molochites" - melochiles, melochites, molochites. The last form survived to the 18th century, until it was supplanted by the modern spelling malachite proposed by the Swedish mineralogist Wallerius. In the first third of the XIX century. in Russia it was customary to write "malachid", less often "malakid".

By composition, malachite is an aqueous carbonic salt of copper - Cu 2 (OH) 2. Copper oxide in malachite contains up to 72%. Its coloring is explained by the presence of a copper ion. It crystallizes in monoclinic syngony. Malachite crystals are extremely rare (very appreciated by collectors), their cleavage is perfect according to the pinacoid. The appearance of crystals is prismatic, needle-like and fibrous; doubles are noted. More often malachite is found in the form of earthy secretions and dense leaky formations. Inside it is composed of radially diverging fibers from coarse and large, up to very small scales. A radially radiant pattern is often combined with a concentrically banded (zonal) color.

There are fine-fibered varieties, sheaf-like, concentric-layered, polycentric, as well as pseudostalactites. Often the stone is contaminated with various impurities, which reduces its decorative qualities.

It happens the other way around - numerous inclusions (dendrites of manganese minerals, grains and fibers of chrysocolla, shatukitta, azurite, elite, brosantite, black smears of tar and copper ore) give it even more decorativeness.

Dense malachite, despite its cavernousness, is an extremely valuable ornamental stone. There are two main ornamental types of stone - radially radiant and dense. The first for its resemblance to the once widespread cotton velvet - plis - and was called plis. The second for the apparent uniformity and cold, a little with a blue, green color - turquoise. Its more decorative variety was identified as patterned. Due to its low hardness (hardness on the Mohs scale 3-4), malachite is easily processed: it is quickly cut, polished and polished well, in the hands of a skilled craftsman it takes the highest mirror polish. The treated surface is fragile - it gradually fades and needs to be updated. Unprocessed malachite is characterized by a faint glass luster, but on a fresh fracture and in veins it often has a silky luster. Malachite is sensitive to heat and unstable with respect to acids, ammonia.

Malachite is a mineral of the oxidation zone of copper sulfide and copper-iron ore deposits occurring in limestones, dolomites, etc. It is formed as a result of the interaction of copper sulfate solutions with carbonate or carbonate waters. Intra-malachite forms occur in karst caves and cavities of ore-bearing limestones, where water with copper bicarbonate is filtered. Common mineral companions of malachite are azurite, chrysocolla, tenorite, cuprite, native copper, oxides and hydroxides Fe and Mn, and secondary minerals Pb and Zn. Pseudomorphs of malachite by azurite, chalcopyrite, cuprite, cerussite, atacamite are known.

Malachite has long attracted the attention of people. From the Neolithic until the Iron Age, it was a stone of artisans: painters and dyers, glassblowers, painters, smelters (smelted copper). Sometimes it was used as ingenious jewelry and simple crafts. The earliest malachite craft is 10,500 years old! This is a modest, simple oval-shaped pendant found in one of the burials of a Neolithic burial ground in the Shanidar Valley (Northern Iraq). In those days, it was valued not beauty, but benefit.

In ancient times, malachite began to appreciate the rarity and beauty, the uniqueness of the picture and the originality of color. Malachite became the material of the artist, and the forms created in it became the object of desire of the nobility. The ancient Greeks decorated malachite with elegant buildings and halls. In ancient Egypt, cameo, amulets and jewelry were made from malachite mined in the Sinai Peninsula. It was used even for summing up the eyes (in the form of a powder).

Only the past of malachite went to the Middle Ages, and European culture mastered it through book traditions, feeding on echoes of its former splendor, legends and traditions that came from the ancient world, and even more mixing truth with fiction, made malachite an amulet, a talisman, endowing it with a special hidden world, hidden meaning. According to the superstition prevalent in medieval Europe, the amulet in the shape of a cross helped facilitate childbirth; the green color of the stone is a symbol of life and growth. Examples show that in the motley and undemanding market of medieval amulets, malachite, an inexpensive stone, was quite popular. They believed that a piece of malachite, attached to a baby cradle, drives away evil spirits, a child overshadowed by this stone sleeps soundly, calmly, without unpleasant dreams. In some regions of Germany, malachite shared with turquoise the reputation of a stone that protected it from falling from a height (rider from a horse, builder from forests, etc.); it was as if he had the ability to foresee disaster - in anticipation of misfortune he was breaking into pieces.

Boethius de Boodt, in his History of Gemstones (1603), wrote that the image of the sun engraved on the stone gives special strength to the malachite talisman. With this sign, malachite guarded from witchcraft charms, evil spirits and poisonous creatures. People believed that malachite could make a person invisible. A drinker from a malachite bowl was able to understand animal languages, etc.

The practical experience of medieval miners knew malachite as a search feature of oxidized copper ores and rich accumulations of metal in copper sandstones.

However, this mineral gained true fame after the discovery of large deposits of malachite in the late XVIII century. in the Urals (previously Ural malachite was used only for copper smelting).

At the end of the XVIII century. - early 19th century many mineral rooms were rich in collections of the Ural malachite: the best were the room of Catherine II in the Winter Palace, the offices of natural scientists P.S. Pallas, I.I. Lepekhin, who visited malachite deposits in the Middle Urals; Count N.P. Rumyantsev owned the largest collection of malachite, which left far behind all the others (they say that in the war of 1812 Napoleon was looking for her, who wanted to take the Rumyantsev malachite to France) ...

In the XIX century. at the Mednorudnyansky and Gumishevsky mines, malachite was mined in large quantities (up to 80 tons annually) and the 19th century became the “golden age of malachite”. The center of his culture moved to Russia, where he found himself with equal success in technology, in scientific knowledge, in art - from small to monumental forms. Malachite is becoming fashionable among the nobility, they talked about him, they decorated the mineral rooms of Russia and Europe.

A special attraction was the malachite giants. Among the most noteworthy are the two monoliths of the Museum of the Mining Institute in St. Petersburg. One weighing 1.5 tons (96 pounds) was transferred here by Catherine II in 1789. In turn, it was presented to her by the heirs of A.F. Turchaninov, the owners of the Gumeshevsky mine, as a fragment of a monolith weighing 2.7 tons (170 pounds). This "fragment" was then estimated at 100,000 rubles. Another block weighing a little more than 0.5 tons came here in 1829 from the owner of the Kyshtym mine in the South Urals L.I. Rastorgueva.

In the late 1920s, at very high prices for malachite and high consumer demand, the stone became a symbol of wealth, a sign of social distinction. Both the imperial court and the highest nobility chased after him, striving, with her inherent vanity, to look no worse than those in power. Having things from malachite becomes the rule of good form.

The quintessence of competition for the possession of the most prestigious form of malachite was the transfer of this stone from the sphere of small "applied" to the colossal things of a palace purpose and architectural and decorative decoration. The first significant phenomenon of the St. Petersburg monumental anthology of malachite was the mosaic decoration of the four-column main hall of the house of P.N. Demidov.

In 1838, the imperial house began a competition with the Demidov in the size of malachite luxury. The Demidov Hall served as the prototype of an even more luxurious decoration of the Empress’s Golden Living Room in the Winter Palace. Facing with malachite pilasters, columns, fireplaces gave her the name Malakhitova. It was created in the years 1838-1839 according to the project of A. P. Brullov by the malachite craftsmen of the Peterhof lapidary factory and the English Store Nichols and Plinke. The thirties of the history of Russian malachite end with this genuine pearl of the Hermitage.

This period was significant in that the malachite affair of Russia gained worldwide recognition in the shortest possible time. Russia has become a trendsetter in everything related to malachite. Russian masters astounded the world with the scale, the perfection of their work, the depth of their artistic vision and perception of malachite. The natural features of malachite - the abundance of large and small voids, caverns, extraneous inclusions, nostrilism - forced him to abandon the usual ideas about the multi-facade beauty of stone, allowing you to make voluminous things.

Russian craftsmen developed a special method of manufacturing products from malachite, called "Russian mosaic", in which pieces of malachite were sawn into thin plates, and a pattern glued to metal or marble was selected from them. Everything made from malachite - from caskets to vases and columns, is carefully selected from thin small tiles. Thousands of pounds of stone were missed by the craftsmen before the disparate tiles merged into a magnificent uniform pattern, giving the impression of solidity of the product.

In the course of work with malachite, several technological types of mosaics were developed:

The first is the simplest, when the field is lined with large polygonal straight-sided tiles, not matched either by drawing or by color. The seams between them are frankly naked, like a frame in a stained glass window. This mosaic imitates a rough breccia.

The second type of mosaic characterizes a slightly more subtle perception of the malachite pattern, although its difference with the first is small. All the tricks here are the same, with the only difference being that one or two sides of each tile are rounded. The rough presence of seams in combination with rounded and polygonal shapes makes the mosaic look like more complex breccias, and sometimes conglomerates.

The third is the most exceptional type of malachite mosaic. The edges of dense large tiles here are processed on a special fixture, where they are given a wavy profile that follows the pattern of malachite.

At the heart of the fourth type of mosaic is not so much a stone as a mastic. It completely covers the decorated field, and then small shapeless tiles with torn fragments or edges cut by nature itself are sunk into it.

The fifth differs from the fourth only in that small round pieces of malachite of high grade, imitating “ocular” types of stone, cut into shapeless tiles recessed into the mastic and into the mastic itself.

Against the background of all these mosaics, the use of malachite with small decorative inserts in Florentine mosaics and even in bulk inlays seems to be of little importance, secondary. Meanwhile, these forms are no less interesting. The development of malachite by European mosaicists (the end of the 18th century) began with them, and the possibilities of its expressive language were discovered in them. Modest in volume forms of malachite of Florentine mosaics, where it is scattered among agates, jasper, cacholong, lapis lazuli, indicates the uniqueness of this stone in the palette of masters.

Mid XIX century - the triumph of malachite and at the same time the last bright stage of its history. During this period, malachite decorations (columns) of St. Isaac's Cathedral in St. Petersburg are completed, work on the malachite fireplace and pilasters of the Grand Kremlin Palace in Moscow ends. 1851 - the triumphal parade of Russian malachite at the first World Exhibition in London.

Since the end of the 19th century, malachite has lost the former glory of the stone of those in power. In small items, it became available to the middle estate, and in monumental items, it appeared to be an expensive, but still semi-precious stone, thereby malachite was deposed from the aristocratic luxury market. Since the 60s, the treatment of malachite has become primarily a matter of the Ural artisan industry. Moscow workshops are turning to malachite less and less, and, finally, completely curtail its processing. And on the waste of huge production of the first half of the 19th century, an entire branch of Russian technological malachite began to develop - the production of malachite paint. A.E. Fersman writes that "... before the revolution in Yekaterinburg and Nizhny Tagil, one could see the roofs of many mansions painted with malachite in a beautiful bluish-green color ...".

In the 20th century, interest in malachite shifted to the field of scientific research. With its study, knowledge of the processes of occurrence of various types of copper and iron-copper deposits is improved, a number of laws ontogeny of minerals are formulated, the foundations of the technology for the synthesis of malachite are laid. Malachite, as before, is loved by collectors. As an ornamental stone, it is rare and mastered only in small forms by jewelers.

Today, malachite is one of the most popular jewelry and decorative stones. Small cabinet decorations, caskets or stands for candlesticks, watches, ashtrays and small figures are made of it. And beads, brooches, rings, pendants made of malachite are valued along with semiprecious stones and are in great demand. On the world market, up to 20 dollars / kg are paid for malachite in raw materials with pieces weighing 600-800 g.

Unfortunately, after many years of continuous production of malachite, the well-known deposits of the Urals - Mednorudyanskoye and Gumeshevskoye - are almost completely developed. Large malachite deposits have been discovered in Zaire (Kolwezi), in the south of Australia, Chile, Zimbabwe, Namibia, the USA (Arizona), malachite is also mined near Lyon in France, however, the color and beauty of the patterns of malachite from foreign deposits cannot be compared to Ural. In this regard, malachite from the Urals is considered the most valuable in the world.

After the discovery of the famous malachite mines in the Urals in 1635, this mineral rightly began to be considered "Russian stone" but to date, the Ural deposits of the Malachites are practically exhausted.

A.A. Kazdym

Candidate of Geological and Mineralogical Sciences,

member of the Moscow Society of Naturalists

Home\u003e Competition

Municipal educational institution

Techen secondary school

Regional competition of educational research of young geologists

"Earth is our home"

Theme: “Malachite”

Completed by: Sharipov Artem

8th grade student

Leaders:

Kozina R.V.

techensky 2010 yearContent- Introduction Stone characteristics History of Malachite stone in our time Conclusion Literature

P. Bazhov, 1936

The first place between Russian works, both in wealth and grace, undoubtedly belongs to products from malachite. The magnificence, amazing completeness with which this precious material has been processed together make up a still unexpected phenomenon in the history of art.

English observer of the Exhibition of All Time, London, 1851 “... Like spring grass under the sun, when it sways in the breeze. So the waves on the green and go. " This seems to the Ural master malachite. In the Urals - his addiction to malachite. It is the Urals who own a monopoly on the best varieties of ornamental malachite. Here it has been mined since ancient times. And they understood better than anywhere else. "Understood" is more than just technological ownership of the material. We are talking about a special - spiritual - comprehension of the beauty of stone. Each people has its own world of fairy-tale heroes, demonic forces - guardians of the bowels. Among the inhabitants of Japan - this is a monstrous spider living deep underground. In Mongolia and on the island of Sulawesi (Celebes), it is believed that wild pigs rule deep in the bowels of the earth. The indigenous inhabitants of South America considered the owner of the bowels of a huge whale that lived in underground waters, in North America - a giant tortoise, in India a giant mole, in Malaysia - a large "gontoba" snake. In other places the gods controlled the secrets of the bowels: in Persia - Dakhnak, on the islands of Polynesia - the giant god Maui ... The Ural miners also had their patron. The Mistress of the Copper Mountain called her. She was the keeper of malachite. So they called her sometimes - Malachitnitsa. She appeared before people in the image of a fabulously beautiful woman with green eyes, dressed in a luxurious malachite dress, with an elegant diadem-kokoshnik, adorned with malachite and precious stones. Her halls were decorated with malachite, diamond and flowers of native copper. This is in her possession sank mines. It was in her kingdom that the corridors of adits and drifts branched, in the dark labyrinths of which, under the light of greasy candles, the army of half-naked, sweaty, exhausted people scurried. What could the Mistress do for the miner? and to delight and astonish the one who loves her: to spread the clay mud of the ore mass and reveal the unbearably clean, sonorous, spring greens of malachite to the eye. It was the attention and compassion of the Malachite that the miners explained every encounter with malachite. Missing malachite - it means the Mistress was angry. And he disappeared as unexpectedly as he appeared. The meeting with him was always unpredictable. So the tradition went along the Urals that only with great kindness, spiritual purity and honesty gives Malachitnitsa his precious stone ... The object my work was the stone malachite. purpose my job is to find out information about malachite as one of the most beautiful minerals. Tasks work:

- Learn about malachite from popular science literature. To study the history of malachite mining from ancient times to the present. To make sure that the most famous in the world is the Ural malachite.

Morning Post, 1851 Gems are ambiguous. Some sides of their way to the technologist, others to the artist, and others to the mineralogist, gemologist, and collector. Each of them - a technologist, artist, scientist - gives life to a stone, thereby forming three powerful branches of its family tree - technological, artistic and research. The nutrient medium of these branches is history itself, social and industrial relations, that is, the whole life of man and society. Over the centuries, the malachite tree of life gained strength. In ancient times, rarity and beauty, the uniqueness of the picture and the originality of color began to be valued in malachite. Malachite became the material of the artist, and the forms created in it became the object of desire of the nobility. The ancient Greeks decorated malachite with elegant buildings and halls. In ancient Egypt, cameo, amulets and jewelry were made from malachite mined in the Sinai Peninsula. It was used even for summing up the eyes (in the form of powder). The Middle Ages got only the past of malachite, and European culture mastered it through book traditions, feeding on echoes of its former magnificence, legends and traditions that have come down from the ancient world, and even more mixing truth with fiction, made malachite an amulet, a talisman, endowing it with a special hidden world, a hidden meaning. According to the superstition prevalent in medieval Europe, the amulet in the shape of a cross helped facilitate childbirth; the green color of the stone is a symbol of life and growth. Examples show that in the motley and undemanding market of medieval amulets, malachite, an inexpensive stone, was quite popular. They believed that a piece of malachite, attached to a baby cradle, drives away evil spirits, a child overshadowed by this stone sleeps soundly, calmly, without unpleasant dreams. In some areas of Germany, malachite shared with turquoise the reputation of a stone protecting it from falling from a height (rider from a horse, builder from forests, etc.); as if he had the ability to anticipate trouble - in anticipation of misfortune he split into pieces. Boethius de Boodt, in his History of Gemstones (1603), wrote that the image of the sun engraved on stone gives a special force to the malachite talisman. With this sign, malachite guarded from witchcraft charms, evil spirits and poisonous creatures. People believed that malachite could make a person invisible. A drinker from a malachite bowl was able to understand animal languages, etc. - The practical experience of medieval miners knew malachite as a search sign of oxidized copper ores and rich accumulations of metal in copper sandstones. With the development of mining at the end of the XVII - beginning of the XVIII century in the deposits of the Kama region, the Middle and Southern Urals, the Orenburg region, the processing center for technological malachite has moved to Russia. This turn in the history of malachite was due to the fact that, in the face of the Urals, against the background of thoroughly worked out deposits of the world, Russia acquired an untouched and truly inexhaustible pantry of copper and iron-copper ores. Who, and when he was the first to pay attention to the ore of Ural malachite, will forever remain in the realm of speculation. In Russian literature of the first half of the 18th century they did not write about it. It was a time when there was no Russian mineralogy yet; Russian original and translated literature on stone was fond of overseas exoticism. Of the five hundred-odd volumes of the first and second third of the 18th century that the author looked in search of the “traces” of malachite, only two gave a short line. Malachite seemed to dissolve in copper and coppery greens. In 1747, a modern form of the stone's name appeared in the book of the Swedish mineralogist Vallerius - malachite (the Russian translation of Vallerius came out in 1763). This new form was adopted by Europe. In the late 50s of the 18th century, Le Sage used it, as applied to the Urals, or, as it was then written, Siberian, stone. With reference to Le Sage in 1761, the Ural malachite describes in detail the French scholar Abbot Chapp d "Oteros, who visited The Urals with the goals of astronomical research in the same year. Provided with magnificent engravings, the description of d "Oterosha is the best publication we know about malachite of the 18th-19th centuries. Published in France, it spread the glory of Russian malachite throughout Europe. They started talking about stone. They were looking for him. They were decorated with mineral cabinets in Russia and Europe. Attempts to classify malachite date back to the 1750s.

* Absolutely pure poplar green malachite,

* With black spots, which is kind of unpleasant,

* Mixed with azure stone or copper blue,

* Malachite with round features or circles, of which greens are sometimes lighter: these circles are similar to the onyx species,

* Light, green-blue or turquoise-colored malachite, which is revered for the best. In 1777, the abbot Fountain established the mineral that makes up malachite, leaving it with the same name. The mineralogical interest in malachite has become a new page in its history. And it’s flattering to realize that it was Russian stone that formed the basis of European gemological knowledge of malachite. Many mineral rooms had rich collections of the Ural malachite: the best were the cabinet of Catherine II at the Winter Palace (the collection was transferred by her to the Mining Institute), and the offices of natural scientists P. S. Pallas, I. I. Lepekhin, who visited the malachite deposits in the Middle Urals; Count N.P. Rumyantsev owned the largest collection of malachite, which left far behind all the others (they say that in the war of 1812 Napoleon was looking for her, who wanted to take the Rumyantsev malachite to France) .In the 60s of the XVIII century, at the time of early acquaintance with malachite, it was called a drip-like, small-droplet-like, descended scum, radiant, fluffy malachite. This is malachite in the manuscript catalog of the mineral cabinet of an unknown owner, which was stored in the library of Count F. Tolstoy and dated 1765. The registry of the mineral cabinet of Count N. P. Rumyantsev in the first third of the 19th century uses the form of malachids, less often malakids, he distinguishes: "beams or stars accumulated needle-like crystals of satin malachide, radiant, spherical, mossy hairy, like stars and bunches, dense malachide. " Descriptions of dense malachite are often accompanied by an assessment: "excellent in the pleasantness of color, extraordinary density and size." Over time, the descriptions become more precise and stricter. Here is, for example, described in 1825 malachite extracted from the Kyshtym mine (South Urals):

"It consists partly of dense, and partly veined malachite; in some places it is covered with glandular lump of yellowish-brown color and quartz; most of it is covered with clay, which is the main breed of this deposit. The exposed parts of malachite are kidney-shaped and droplet-like species of beautiful green color, characteristic of malachite. its interior is marked by caves, the walls of which are covered either with a very delicate, velvet-like, malachite or black substance that forms very small, ball-like particles. When this piece was brought to the surface (165 kg.), it was not damaged at all, and how beautiful ore can serve as an adornment of the best mineral collection. "Yet, especially in the first quarter of the 19th century, collecting malachite, as well as collecting mineral cabinets, is becoming not only a necessity, but also a fashion." Moscow Telegraph "is Pushkin’s fashion magazine time - in 1831 shared with the reader:

“Paris dandies, for example, are now collecting different collections: a different shell, another bird, a third animal ...” In Russia, stone was preferred over all this. Following the scientists, writers, artists, architects, dignitaries began to collect it. And, of course, no one passed by malachite. This period was significant in that the malachite business of Russia gained worldwide recognition in the shortest possible time. Russia has become a trendsetter in everything related to malachite. Russian masters astounded the world with the scale, the perfection of their work, the depth of their artistic vision and perception of malachite. The natural features of malachite - the abundance of large and small voids, caverns, extraneous inclusions, nostrilism - forced him to abandon the usual ideas about the multi-façade beauty of stone, allowing you to make voluminous things. Russian craftsmen developed a special method for manufacturing products from malachite, called "Russian mosaic ", in which pieces of malachite were sawn into thin plates, and from them was selected a pattern glued to metal or marble. Everything made from malachite - from caskets to vases and columns, is carefully selected from thin small tiles. Thousands of pounds of stone were missed by the craftsmen before the disparate tiles merged into a magnificent uniform pattern, giving the impression of solidity of the product. During the work with malachite several technological types of mosaics were developed:

“The first is the simplest when the field is lined with large polygonal, straight-sided tiles, not matched either in design or color. The seams between them are openly exposed, like a frame in a stained glass window. This mosaic imitates a rough breccia.

"The second type of mosaic characterizes a slightly more subtle perception of the malachite pattern, although its difference with the first is small. All the methods here are the same, with the only difference being that one or two sides of each tile are rounded. The rough presence of seams in combination with rounded and polygonal shapes makes a mosaic similar to more complex breccias, and sometimes conglomerates.

"The third is the most exceptional type of malachite mosaic. The edges of dense large tiles are processed on a special fixture, where they are given a wavy profile that repeats the pattern of malachite.

“The basis of the fourth type of mosaic is not so much a stone as a mastic. It completely covers the decorated field, and then small shapeless tiles with torn fragments or edges cut by nature itself are embedded in it.

"The fifth differs from the fourth only in that small round malachite pieces of up to 7-8 mm in diameter, imitating" ocular "grades of stone, cut into or into the mastic itself, cut into or into the mastic itself, imitating the" ocular "types of stone. The use of malachite by small decorative inserts into Florentine mosaics and even into volumetric inlays seems to be of little importance, these forms are of little importance, meanwhile, these forms are no less interesting. its expressive language. The modest in volume forms of the malachite of Florentine mosaics, where it is scattered among agates, jasper, cacholong, lapis lazuli, testifies to the uniqueness of this stone in the palette of masters. Yekaterinburg and Nizhny Tagil, one could see the roofs of many mansions painted with beautiful malachite in beautiful bluish-green color. "In the twenties, contemporaries noted a rich collection of malachite" Museum "P. P. Svinin - one of the attractions of Pushkin Petersburg. The collection was part of the Mineral Cabinet of the collector, located in the house on Mikhailovskaya Square. The office was visited by foreign guests of St. Petersburg. A. Humboldt visited him. (In 1834, P. Svinin announced the sale of the Museum, and the collection of malachite was auctioned.) The unique malachites were located in the offices of A. Stroganov and V. Kochubey. The idea of \u200b\u200bwhat a large private collection of malachite of those years could have been is given by the collection of Count N.P. Rumyantsev that has come down to us (it was kept at the Moscow City State Administration). Two cabinet registries, 1828 and 1845, contain interesting material on the course of acquaintance with the Ural stone. The first - the so-called Large format collection - notes the supply of ore from the Turyinsky, Bogoslovsky and Gumeshevsky mines, malachite of copper sandstones of Prikamye, rare malachite samples on quartz of the Berezovsky gold deposit. The second collection of the Small format contains descriptions of malachite from the mines of the Zlatoust mountain district - a special attraction of the Ural malachite . The collection as a whole is replete with all types of stone: radiant films, rosette-shaped and fan-shaped needle crystals, sheaf-shaped radiant bunches, stalactites, simple bud-shaped crusts and magnificent buds, correctly formed crystals and ore of oxidized copper ore, where malachite-tear-shaped balls settled in voids fibrils, unrealistically green, with a soft velvety surface slices of a petrified tree, the voids of which are made of malachite crystals or the same spherulite balls. A special attraction was the malachite giants. They were saved in state assemblies as a national treasure. Among the most noteworthy are the two monoliths of the Museum of the Mining Institute in St. Petersburg. One weighing 1.5 tons (96 pounds) was transferred here by Catherine II in 1789. In turn, it was presented to her by the heirs of A.F. Turchaninov, the owners of the Gumeshevsky mine, as a fragment of a monolith weighing 2.7 tons (170 pounds). This "fragment" was then estimated at 100,000 rubles. Another block weighing a little more than 0.5 tons came here in 1829 from the owner of the Kyshtym mine in the South Urals L. I. Rastorguev. Another malachite monolith weighing about 0.5 tons is stored in the Nizhny Tagil Museum of History and Local Lore. He inherited from the large mining of the 1830-1840s in the Mednorudnyansky mine. The mass from the collection of the Sverdlovsk Museum of History and Local Lore is not inferior to it in mass.

Malachite through the ages

Mid XIX century - the triumph of malachite and at the same time the last bright stage of its history. During this period, malachite decorations (columns) of St. Isaac's Cathedral in St. Petersburg are completed, work on the malachite fireplace and pilasters of the Grand Kremlin Palace in Moscow ends. 1851 - the triumphal parade of Russian malachite at the first World Exhibition in London.Since the end of the 19th century, malachite has lost the former glory of the stone of those in power. In small items, it became available to the middle class, and in monumental items, it appeared to be an expensive, but still semi-precious stone, thereby malachite was deposed from the aristocratic luxury market. Since the 60s, the treatment of malachite has become primarily a matter of the Ural artisan industry. Moscow workshops are turning to malachite less and less, and, finally, completely curtail its processing. And on the waste of huge production of the first half of the 19th century, an entire branch of Russian technological malachite began to develop - the production of malachite paint.

Malachite as a decoration

Everyone who saw products from malachite will agree that this is one of the most beautiful stones. Overflows of all kinds of shades from blue to deep green in combination with a fancy pattern give the mineral a unique identity. Depending on the angle of incidence of light, some areas may appear lighter than others, and when the sample is rotated, a “run-through" of light is observed — the so-called moire or silky tint. According to the classification of academician AE Fersman and the German mineralogist M. Bauer, malachite occupies the highest first category among semiprecious stones, along with rock crystal, lapis lazuli, jasper, agate.

The name comes from the Greek mineral malache - malva; the leaves of this plant have, like malachite, a bright green color. The term "malachite" was introduced in 1747 by the Swedish mineralogist J.G. Vallerius. Malachite has been known since prehistoric times. The oldest known malachite product is a pendant from a Neolithic burial ground in Iraq, which is more than 10.5 thousand years old. Malachite beads found in the vicinity of ancient Jericho, 9 thousand years. In ancient Egypt, malachite mixed with fat was used in cosmetics and hygiene. His eyelids were stained green: copper, as you know, has bactericidal properties. Powdered malachite was used to make colored glass and glaze. Malachite was also used for decorative purposes in Ancient China. In Russia, malachite has been known since the 17th century, but its mass use as a jewelry stone began only in the late 18th century, when huge malachite monoliths were found at the Gumeshevsky mine. Since then, malachite has become a ceremonial facing stone decorating the palace interiors. From the middle of the 19th century For these purposes, tens of tons of malachite were brought from the Urals annually. Visitors to the State Hermitage can admire the Malachite Hall, the decoration of which went to two tons of malachite; there is also a huge malachite vase. Products from malachite can also be seen in the Catherine Hall of the Grand Kremlin Palace in Moscow. But the columns of the altar of St. Isaac's Cathedral in St. Petersburg about 10 meters high can be considered the most remarkable in beauty and size of the malachite item. It seems uninitiated that both the vase and the columns are made of huge solid pieces of malachite. This is actually not the case. The products themselves are made of metal, gypsum, other materials, and only on the outside they are lined with malachite tiles cut from a suitable piece - a kind of “malachite plywood”. The larger the original piece of malachite was, the larger the tiles were able to cut out of it. And to save valuable stone, the tiles were made very thin: their thickness sometimes reached 1 mm! But the main trick was not even that. If you simply lay some kind of surface with such tiles, then nothing good will come of it: after all, the beauty of malachite is largely determined by its pattern. It was necessary that the pattern of each tile was a continuation of the previous pattern. A special method of cutting malachite was perfected by the malachite craftsmen of the Urals and Peterhof and therefore it is known throughout the world as “Russian mosaic”. In accordance with this method, a piece of malachite is sawn perpendicular to the layered structure of the mineral, and the resulting tiles seem to “unfold” in the form of an accordion. In this case, the pattern of each subsequent tile is a continuation of the previous pattern. With this sawing, a large area cladding with a single ongoing pattern can be obtained from a relatively small piece of mineral. Then, using special mastic, the tiles were pasted over the product, and this work also required the greatest skill and art. Masters sometimes managed to “stretch” a malachite pattern through a rather large product. In 1851, Russia took part in the World Exhibition in London. Among other exhibits was, of course, the “Russian mosaic”. The Londoners were especially struck by the doors in the Russian pavilion. One of the local newspapers wrote about this: "The transition from the brooch that malachite adorns like a gem to colossal doors seemed incomprehensible: people refused to believe that these doors were made of the same material that everyone was accustomed to consider as a jewel." A lot of jewelry is also made from Ural malachite ( Malachite Box Bazhov). Malachite in our timeA new tourist route is being developed in the Sverdlovsk region. Anyone who wants to can feel like a worker from the Demid era: go down into a real quarry where they extracted malachite, try their luck by sifting river sand containing platinum.

The route "Following the Humboldt" is being developed by the editors of the regional travel magazine and the staff of the Nizhny Tagil Museum-Reserve. Together with their like-minded people, they conducted their first test drive along the new hiking trail.

A dedication to the outstanding German naturalist Alexander von Humboldt suggests itself. He became one of the first explorers of the Urals. The scientist came to Russia 180 years ago at the invitation of the Russian Emperor Nicholas I to draw up a report on the reserves of platinum and gold in the Urals.

The indefatigable Humboldt, then an elderly man who had thoroughly studied South America, for which he was called the "second Columbus", could not rest on just researching precious metals deposits. He traveled to the Urals, Volga region, Siberia, collected a lot of scientific information from the fields of geography, geophysics, botany, ethnography, meteorology. In a word, now “following the Humboldt trail” in Russia you can go very far and for a long time. The developers of the new route did not try to grasp the immensity, but even with this condition, the trip takes a whole day.

The expedition begins with a visit to the museum of local lore in Nizhny Tagil. Tourists are personally convinced of the authenticity and power of the Ural riches. What are the only samples of steel twisted into a knot in a cold form? Such exhibits were taken by Demidovs to foreign exhibitions. Ural gems, malachite caskets and other slightly forgotten symbols of the support edge of the state are here in originals and in all its glory.

Tourists try to see all these riches in the rock dumps, going down to the quarry of Vysokaya Mountain. This is the second point on the route. Copper and iron ore have been mined up to the present day. On the quarry, the remnants of larch adits sticking directly from its walls are impressive. They were built back in Demid times. Tier after tier, the workers dug up Mount Vysokaya for more than two hundred years. The mines went 280 meters underground. At the bottom of the quarries, today you can find pieces of rock with green veins of malachite. The expedition members tried to reincarnate as mine workers. To do this, those who wished were given a real old Kyle, who had previously crushed the breed.

A look at the Ural mountains "from within" is replaced by a look "from above." Tourists on chairlifts go to the top of Belaya Mountain. In winter, there is a ski resort, in summer, among extreme stones on steep descents, extreme cyclists test their fate. At an altitude of more than 700 meters above sea level, a geodetic sign is established - the border between Europe and Asia. In the Urals there is no shortage of such signs, but not all of them have the solid status of a real geodetic document.

In the fifties of the 19th century, about a hundred gold and platinum mines operated in the Urals. The participants of the “trial” expedition were lucky to see the work of modern miners. Platinum near Nizhny Tagil, in particular, in the area of \u200b\u200bthe village of Uralets, is still being washed. What most strikes us ignorant people: they wash as they did one hundred and fifty years ago. The first stage - sifting of large pieces of rock - takes place under the pressure of a water cannon in a dredge. Sand with the smallest silver crumbs settles and gets stuck in rubber mats laid on pallets. And then the sand is washed in buckets. A mining worker guy demonstrates a master class. "Really, you wash so manually?" - not believing their eyes, ask the crowded members of the expedition. The miner nods silently. “Humboldt would be in shock,” one of us jokes.

Everyone is allowed to try to wash the platinum sand. The work seems to be simple, but skill is required here. Of course, you don’t have to take precious crumbs with you. With this strictly - precious metals are exported under serious protection.

It was in the nineteenth century that platinum from the mines was accompanied by one clerk with a revolver. There were enough placers for both official miners and “hitters”. A few years after the abolition of serfdom in the Urals, platinum fever even began. Mining and processing of precious metal was allowed to private individuals. Free circulation of crude platinum in the country and its export abroad were allowed.

Such expanse, as before, cannot be expected by modern hunters of luck. Now you can wash yourself a little valuable platinum crust except during such an expedition. And even then, with luck.

The trip ends in the homeland of writer Dmitry Mamin-Sibiryak - in the village of Visim.

The main enthusiast and route designer, travel magazine editor Elena Elagina, says that in order to create a full-fledged tour, you need to thoroughly work out the program, get the go-ahead from the owners of the quarry, the management of the ski resort. Finally, calculate and optimize all costs: "Transport for guests from Yekaterinburg is not cheap. If this trip was paid, it would cost each of us 2 thousand rubles."

The Ministry of Sports and Tourism in the Sverdlovsk region believes in the promise of the route. “The Urals should attract with what is not in the capitals. Our uniqueness is mineralogical tourism, everyday life,” says Natalya Sergeeva, chief specialist in tourism of the regional ministry of sports. “Therefore, we are ready to help organizationally promote this route. But like any tourist product, it’s will work when travel agencies begin to sell it. "

“Such tours are not a vacation for everyone,” summarizes Andreas Förster, head of the Russian-German project “Following the Humboldt in Russia.” “Most tourists around the world prefer to sunbathe on the beaches rather than travel through careers. But the world isn’t there’s a lot of similar routes. For example, I saw ancient galleries only here. Undoubtedly, we need a good information component so that it is not just a walk, but also an immersion in history. "

ConclusionThere are many minerals on earth. They amaze us with a multifaceted palette of shades, their splendor and grandeur. They idolize, admire them, compose poems. But our choice fell on malachite. He impressed primarily with his story. And when we saw the stone itself, photographs of jewelry and stone products, we were conquered by it. And we were convinced that the Ural malachite is the most famous in the world. And how beautifully A.E. said about him. Fersman: “Among the green gems there is another stone that can rightfully be considered Russian, since only in our country are those huge deposits discovered that have made it famous all over the world. This is malachite, a stone of bright, juicy, cheerful and at the same time silky-soft greens "And, maybe, once I can go along the Humbolt route and touch the most famous Ural malachite in the world, and with it the history of my native land Literature:

1. Godovikov A.A. Mineralogy 2. "Russian newspaper"

3. Semenov VB "Malachite", t.1,2 Sverdlovsk, 1987.

4. Fersman A.E. "Stories of gems" L., Detgiz, 1952. "5. Schumann V." The world of stone. Precious and ornamental stones. "

\u003e D-579 Show / Hide Text

D-579 (-). 1. The main idea of \u200b\u200bthe text is that nothing in nature can compare with malachite.

It has long been customary to look for analogies to the color of the Ural malachite in wildlife. But we still have to admit that the colors of malachite do not have full conformity in nature.

[\u003d] that (\u003d).

The green of trees and flowers is born of solar heat. When we peer at a leaf of a plant, we admire the harmony created by nature itself.

[- \u003d]. then (\u003d).

Strengths of green leaf are always softer than the color of the leaf itself. "These streaks pierced by sunlight seem light and delicate, like a cobweb.

The greens of malachite are heavy and cold, just as the stone itself is heavy and cold in nature.

[-SC ^ and C B]. like (C_C_

Green in nature calms the eye, while in malachite it is restless, dynamic. Coloring is distributed unevenly, by impulses. Often around the bright shades of green circling, flashing and fading, glaze-green and bluish-green blotches.

2. Openwork - through, fine-mesh. An analogy is a form of inference when, on the basis of the similarity of two objects, a conclusion is drawn about their similarity in other respects.

Dynamic - in motion.

An impulse is an incentive moment, an impulse that causes some action.

4. [But one still has to admit], (that the paints of malachite do not have full conformity in nature).

(what).

What is a simple union

Subordinate

(When we peer at a leaf of a plant), [we admire

reason about.

harmony, created by nature itself "].

(When), [then, ImacLi ^ l].

When ... then a union

Composite

Subordinate

[The greens of malachite are heavy and cold], (how heavy and cold the stone itself is by nature).

(as).

Like - Simple Union

Subordinate

5. Since ancient times - an adverb. Adverb of time. Immutable

It is customary to search (when?) For a long time.

Born - communion. N.f. - born. From the verb to give birth.

Fasting, signs: passive, relapsing, owls. view, past. time.

Nepost, signs: short, units hours, wives genus. Greens (what?) Is born.

Created - Communion. N.f. - created. From the verb create.

Fasting, signs: passive, irrevocable .. owls. view. past time.

Nepost, signs: complete, unit number, wives genus. tv pad.

Harmony (what?) Created.

Always an adverb

Adverb of time

Immutable

Softer (when?) Always.

Laced - communion. N.f. - permeated. From the verb to permeate

Fasting, signs: passive, irrevocable .. nesov. view. past time.

Nepost, signs: complete, pl. number to them. pad. Streaks (what?) Pierced.

Roughly - an adverb. Adverb of a way of action. Immutable

It is distributed (how?) Unevenly.

Often - an adverb. Adverb of time. Immutable Spin (when?) Often.

Flaring up - the participle. From the verb flash. Imperfect species. Immutable Spin (how?) Flashing.

Fading away - participle. From the verb fade away.

g

Immutable Imperfect appearance. Spin (to and to?) Fading away.

Probably every malachite knows every person who has read Pavel Bazhov’s tales about the mistress of the Copper Mountain, who owned all the Ural treasures hidden under the ground, in childhood. The whole story of this gem is composed of mystical events. In ancient times, people believed that malachite conducts the forces of the universe to Earth. A large number of beliefs and legends are associated with this stone, for example, that it can make a person invisible. It was believed that the Ural malachite can fulfill wishes!

The name "malachite": origin

The roots of the word malachite go back to Greek. There are two versions of the interpretation of this noun. According to one, the Greeks called this stone because of its rich color - μολόχα - "green flower". Another version says that the name comes from the word μαλακός - “soft”.

Indeed, malachite is distinguished by its fragility, it is unstable to external influences. Jewelers claim that the real Ural malachite loses its color and grows dull, even if dust just sits on it! It is noted that the softness of this mineral can turn into its advantage. After all, malachite lends itself well to polishing and polishing.

Colors characteristic of malachite

The mineral has a pleasant green color. In nature, there are three main shades: yellow-green, saturated green and almost colorless. However, unique specimens come across, the color of which varies from turquoise to emerald.

Stone history

The oldest malachite jewelry was found in Iraq 10.5 thousand years ago. And in Israel, malachite beads were found, whose age is nine millennia. In ancient Rome, malachite was used to create amulets and amulets. This mineral was extremely popular in China and India. In addition, it was used to make paints that did not lose their brightness for a long time. Proof of this are the tombs of the pharaohs. And the beauties from Ancient Egypt made malachite powder of eye shadow.

Ural malachite: the history of fishing in Russia

Until the 18th century, malachite was found only in the form of small nuggets. This mineral became popular only after the development of the Ural deposits began in Russia. It was the Russian miners who were able to find blocks of mineral that weighed several hundred tons. But the heaviest block had a weight of 250 tons. Discovered it in 1835.

The first malachite deposit was discovered in the forties of the 18th century. It is called Gumeshevskoe and is located at the source of the Chusovaya River. Thanks to the discovery of that mine in Russia, the production of small jewelry began. Rings and beads, earrings and pendants - Ural malachite stone was usually used together with other stones, most often precious.

The flowering of the field began after the discovery of the Mednorudnyanskoye field. It was then that a unique style of manufacturing products from this stone appeared, which was called Russian mosaic. Skillful stone-cutters sawed the stones into the thinnest plates, picked up patterns and stuck on the base. After the grinding process began. Russian craftsmen created such Ural products from malachite that no observer could even doubt the solidity of the products.

The reserves of the Ural malachite were so rich that some craftsmen could afford the careless handling of this mineral. There are cases when the malachite crumbs, with which the craftsmen refused to work, fell into the pits in the pavements. Today, such wastefulness seems like a real madness, because even the smallest pieces are a real miracle.

The year 1726 was marked by the fact that the first workshop for processing malachite appeared in the Urals. And in 1765, by decree of Catherine the First, the first factory of the Ural malachite, the Yekaterinburg lapidary, was opened. At the same time, it was a complex for the extraction and processing of this stone, a center for stone cutting and an educational institution for several generations of craftsmen.

The popularity of the mineral

This stone has become an adornment of houses of Russian and European nobility. It was even used to decorate rooms, for example, the Malachite living room of the Winter Palace. The artistic value of this masterpiece of Russian architecture is difficult to overestimate. The drawing is so skillfully selected that the joints between the plates are completely impossible to see. The columns of St. Isaac's Cathedral were lined with malachite. In the chambers of wealthy people, one could find such things as a vase from the Ural malachite, watches, snuff-boxes, caskets and even fireplaces and countertops made of this mineral.

By the way, at that time it was very fashionable to collect interesting samples of various minerals, including malachite. Know even competed among themselves. The title of owner of the best collection was rightfully received by Empress Catherine II.

Types of Malachite

There are two types of Ural malachite - plisse and turquoise. Plisovy malachite is brittle, and therefore worse treatable. It is not used to create jewelry. Most often, this species is of interest to mineral scientists. Lovers and experts collect samples of this mineral. A more common type of malachite is turquoise. Its structure is unique: asymmetric stripes and circles create a bizarre pattern. Unique green patterns are appreciated by collectors and jewelers.

The end of the malachite era

At the end of the 19th century, this delicious mineral became available not only to very wealthy people, but also to nobles. Competitions in the number of malachite items in houses ceased, the mineral became less commonly used in interiors. Apply malachite steel for the manufacture of paint, which covered the roofs of houses.

The revolution of 1917 led to the fact that stone production decreased significantly. This was due to the fact that the two main deposits - Mednorudnyanskoye and Gumeshevskoye - were severely depleted. At the end of the 19th century, the Gumeshevsky mine was seriously flooded. And therefore, now this place is visited exclusively by extreme people. The Mednorudnyanskoye deposit is still operating, only copper is not mined here, but malachite. Today, Ural malachite is practically not found here, and therefore it is valued more and more.

Malachite business today

The Urals is far from the only place in the world where malachite deposits were discovered. Development is also ongoing in Altai. By the way, sometimes there are samples of Altai malachite, which in terms of beauty and quirkiness of the rings practically do not differ from samples of the Ural mineral. The modern leader in the supply of malachite is the Republic of Congo. Malachite mined here differs from the Urals in the pattern consisting of even stripes. The mineral is mined in the UK, Chile, Australia, France and Cuba. However, the stones mined in these mines are significantly inferior in their external qualities to the Ural malachite.

Does malachite from the Urals have a future?

Experts have established that all the world's reserves of malachite can be attributed to the same type, and the appearance of the mineral is associated with the zonal oxidation of copper ores. That is, the probability that new deposits of malachite can be found in the Urals is extremely high.

For several years, Grigory Nikolayevich Vertushkov, professor at Sverdlovsk University, has been collecting information that is somehow connected with copper and malachite deposits. He is sure that the researchers were wrong and, in fact, the reserves of the Ural mines are not depleted. Grigory Nikolayevich claims that the two deposits are untouched by the deep reserves of this unique mineral.

The most famous products from malachite

The Malachite Hall mentioned above is just a storehouse of products from this mineral. Here you can see vases and tables, bowls and columns. It all took about two hundred pounds (by the way, 1 pound is 16.38 kg). Almost all the products here are made in the style of “Russian mosaic”. 1,500 pounds of malachite was needed for lining the columns of the largest Orthodox church in St. Petersburg - St. Isaac's Cathedral.

In the Pitti Palace, located in Florence, there is a malachite table, preserved from the heyday of the malachite craft in Russia. For the London exhibition in 1851, an incredible collection of items was made: doors, tables and chairs, grandfather clocks, vases and a fireplace.

Who should wear malachite products

To whom is Ural malachite suitable? Astrologers advise wearing jewelry from this stone to representatives of such zodiac signs as Capricorn, Libra, Scorpio and Taurus. Malachite is suitable for people of creative professions. This stone will bring benefit to writers, artists, artists. Malachite will help women to remain youthful and attractive for a long time.

How to distinguish real malachite from fake?

Ural malachite, the photo of which you have already seen, is very popular, and therefore its synthetic analogue appeared on the market. To create a fake, plastic and glass are used.

How to distinguish a natural stone from a fake?

- Real malachite is cool to the touch. Imitation plastic - warm.

- Glass stone is distinguished by the presence of transparent inclusions on the surface.

- Imitations that are made on the basis of other stones with the addition of painting and varnish can be distinguished from natural stone by dropping liquid ammonia on them: real malachite will acquire a blue tint, and the fake will not change.

- You can distinguish genuine Ural malachite from a fake using vinegar or lemon juice. True, the surface of natural stone after such a check will begin to bubble strongly.

Magical and healing properties of the Ural malachite

The green mineral was given magical properties back in the Middle Ages. Small pieces of malachite were hung over the crib, believing that they would drive away evil spirits and the baby would sleep peacefully. To protect an adult, malachite was engraved - usually in the form of the sun.

It was believed that malachite is a good helper in love rituals. He was often mentioned in fortune-telling and magic books as a means of attracting and holding love. Traditional healers with the help of malachite treated allergies and skin diseases, asthma and migraines.